Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten

| The Steel Helmet, League of Front-Line Soldiers | |

|---|---|

| Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten | |

The logo of the organization | |

| Also known as | Der Stahlhelmbund |

| Federal Leader | Franz Seldte[1] Theodor Duesterberg (Deputy) |

| Foundation | 25 December 1918 |

| Dissolved | 7 November 1935[a] |

| Merged into | Sturmabteilung |

| Group(s) |

|

| Motives | Maintain peace and order and foster front-line comradeship.[2] |

| Headquarters | Berlin, Germany |

| Newspaper | Der Stahlhelm (central organ)[3] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right[9] |

| Slogan | Front Heil! (unofficial, popular) |

| Anthem | Stahlhelm-Bundeslied[10] (lit. 'Steel Helmet League Anthem') |

| Major actions | Stahlhelm Putsch (1933) |

| Size | 1,500,000 (1933 est.) |

| Part of |

|

| Allies | Deutschnationale Volkspartei[14] |

| Flag |  |

Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten (German: 'The Steel Helmet, League of Front-Line Soldiers'), commonly known as Der Stahlhelm ('The Steel Helmet'), was a revanchist ex-serviceman's association formed in Germany after the First World War. Dedicated to preserving the camaraderie and sacrifice of German frontline soldiers, it quickly evolved into a highly politicised force of ultranationalist resistance, opposed to the democratic values of the Weimar Republic. By the 1920s, Der Stahlhelm had become a mass movement with hundreds of thousands of members, ideologically aligned with völkisch-nationalist currents: anti-Marxist, anti-Semitic, determined to reverse the Treaty of Versailles, but distinguished from Hitler's National Socialists by their support for a Hohenzollern restoration. As a cultural and political formation, Der Stahlhelm was instrumental in undermining democratic legitimacy and laying the ideological groundwork for the rise of the Nazi regime by whom it was eventually absorbed. After the Second World War, a Stahlhelm network was re-established in West Germany. Following a history of supporting fringe nationalist parties, the last functioning local association dissolved itself in 2000.

Name

[edit]The Stahlhelm (steel helmet) and the black-white-red imperial flag were deeply symbolic to the Der Stahlhelm organization, embodying its nationalist and militarist identity. The helmet, used as both the group’s name and emblem, recalled the front-line experiences of World War I soldiers and symbolized sacrifice, masculine toughness, and the unity of the Frontgemeinschaft—a stark contrast to the party politics and democratic values of the Weimar Republic, which the organization despised.[16] Detlev Peukert noted that the steel helmet became a "[...] fetishized emblem of national renewal through military unity."[17] The black-white-red flag of the former German Empire, used in place of the Weimar Republic’s democratic black-red-gold banner, symbolized Der Stahlhelm’s allegiance to the imperial past and rejection of republican governance. It served as a visual statement of monarchist loyalty and nationalist pride, directly opposing the postwar political order.[18] George L. Mosse described the use of the imperial flag as a theatrical reaffirmation of Germany’s militaristic traditions and a nostalgic expression of longing for unity under the monarchy.[19] Together, these symbols reflected Der Stahlhelm’s anti-democratic ideology and its desire for a return to an authoritarian, martial German state.

History

[edit]Historical background

[edit]

Der Stahlhelm was formed on 25 December 1918 in Magdeburg, Free State of Anhalt, Germany, by the factory owner and First World War–disabled reserve officer Franz Seldte. After the 11 November armistice, the Army had been split up and the newly established German Reichswehr, according to the Treaty of Versailles, was to be restricted to no more than 100,000 men. Similar to the numerous Freikorps, which upon the Revolution of 1918–1919 were temporarily backed by the Council of the People's Deputies under Chancellor Friedrich Ebert, Der Stahlhelm ex-servicemen's organization was meant to form a paramilitary organization.

The league was a rallying point for revanchist and nationalistic forces from the beginning. Within the organization a worldview oriented toward the prior imperial regime and the Hohenzollern monarchy predominated, many of its members promoting the stab-in-the-back legend (Dolchstosslegende), the charge that the democratic politicians who had accepted the Kaiser's abdication and sued for peace had betrayed an undefeated German army. Its journal, Der Stahlhelm, was edited by Count Hans-Jürgen von Blumenthal, later hanged for his part in the 20 July plot of 1944. Financing was provided by the Deutscher Herrenklub, an association of German industrialists and business magnates with elements of the East Elbian landed gentry (Junker). Jewish veterans were denied admission and formed a separate Reichsbund jüdischer Frontsoldaten. The Deutscher Herrenklub functioned as a nexus for Germany's conservative elite, including prominent figures from heavy industry, finance, and the landed aristocracy. Their funding of Der Stahlhelm aligned with their shared objectives of promoting monarchism, nationalism, and opposition to the Weimar Republic's democratic institutions. This alliance aimed to counteract the perceived threats of socialism and liberalism, striving to restore traditional German values and authority structures.

Limited role in the Kapp Putsch

[edit]While not directly involved in planning or executing the Kapp Putsch, Der Stahlhelm sympathized with its objectives and provided ideological support. Some regional units may have offered assistance or coordinated with Freikorps units during the uprising, but the organization's involvement was not central to the coup's operations. Historian Larry Eugene Jones notes that Der Stahlhelm "shared the anti-republican, anti-socialist, and nationalist sentiments that motivated the Kapp putschists."[20] This alignment illustrates the organization's role as part of the broader right-wing nationalist network that sought to undermine the Weimar Republic.

From 1920 onwards

[edit]After the failed Kapp Putsch of 1920, the organization gained further support from dissolved Freikorps units. In 1923 the former DNVP politician Theodor Duesterberg joined Der Stahlhelm and becoming Seldte's deputy and leadership rival. In 1923, Stahlhelm units were actively involved in the formally passive resistance struggle of paramilitary formations against the French occupation of the Ruhr area. These units were responsible for numerous acts of sabotage on French trains and military posts. One of the volunteers operating in the Ruhr area was Paul Osthold, who headed the German Institute for Technical Work Training (DINTA) in the 1930s and became one of the leading representatives of German employers' associations in the Federal Republic of Germany.[21] From 1924 on, in several subsidiary organizations, veterans with front line experience as well as new recruits would provide a standing armed force in support of the Reichswehr beyond the 100,000 men allowed. With 500,000 members in 1930, the league was the largest paramilitary organization of Weimar Republic. In the 1920s Der Stahlhelm received political support from Fascist Italy's Duce Benito Mussolini.[22]

Although Der Stahlhelm was officially a non-party entity and above party politics, after 1929 it took on an anti-republican and anti-democratic character. It sought a presidential dictatorship as a prelude to a Hohenzollern restoration and the creation, through expansion to the East, of a Greater Germanic People's Reich. This was seen as possible only through suppression of "Marxism" and the "mercantilism of the Jews" and of the general liberal democratic worldview in which these were tolerated.[23]

In 1929 Der Stahlhelm supported the "Peoples' Initiative" of DNVP leader Alfred Hugenberg and the Nazis to initiate a German referendum against the Young Plan on World War I reparations. In 1931 they proposed another referendum for the dissolution of the Prussian Landtag. After both these referendums failed to reach the 50% necessary to be declared valid, the organization in October 1931 joined another attempt of DNVP, NSDAP and Pan-German League to form the Harzburg Front, a united right-wing campaign against the Weimar Republic and Chancellor Heinrich Brüning. However, the front soon broke up and in the first round of the 1932 German presidential election, Theodor Duesterberg ran as Der Stahlhelm candidate against incumbent Paul von Hindenburg and Adolf Hitler. Duesterberg's candidacy attracted the votes of industrialists who would have otherwise voted Hindenburg for fear of Hitler. On 1 March the National Rural League (RLB), despite the best efforts of Hindenburg's campaigners, encouraged its followers to vote either Duesterberg or Hitler in order to remove the government of Brüning.[24] Facing a massive Nazi campaign reproaching him with having Jewish ancestry he only secured 6.8% of the votes cast.[25]

Absorption into the SA

[edit]

After the Nazi seizure of power on 30 January 1933, the new authorities urged for a merger into the party's Sturmabteilung (SA) paramilitary organization. Seldte joined the Hitler Cabinet as Reich Minister for Labour, prevailing against Duesterberg. Der Stahlhelm still tried to keep its distance from the Nazis, and in the run-up to the German federal election of 5 March 1933 formed the united conservative "Black-White-Red Struggle Front" (Kampffront Schwarz-Weiß-Rot) with the DNVP and the Agricultural League, reaching 8% of the votes.

On 27 March 1933, the SA attempted to disarm Stahlhelm members in Braunschweig, who under the command of Werner Schrader had forged an alliance with scattered republican Reichsbanner forces. The violent incident initiated by Nazi Minister Dietrich Klagges and later called Der Stahlhelm Putsch was characteristic of the pressure applied by the Nazis on Der Stahlhelm in this period, mistrusting the organization due to its fundamentally monarchist character. In April Seldte applied for membership in the NSDAP and also joined the SA, from August 1933 in the rank of an Obergruppenführer.

On 27 April 1933, Seldte had officially declared Der Stahlhelm subordinate to Hitler's command. The attempts by the Nazis to integrate Der Stahlhelm succeeded in 1934 in the course of the "voluntary" Gleichschaltung (English: Synchronization) process: the organization was renamed Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher frontkämpfer-Bund (Stahlhelm) (English: National Socialist German Combatants' Federation (Stahlhelm)) (NSDFBSt) while large parts were merged into the SA as Wehrstahlhelm, Reserve I and Reserve II contingents.

The remaining NSDFBSt local groups were finally dissolved by decree of Adolf Hitler on 7 November 1935. Seldte's rival Duesterberg was interned at Dachau concentration camp upon the Night of the Long Knives at the beginning of July 1934, but released soon after.

Role in the July 20th Plot

[edit]Although Der Stahlhelm was forcibly absorbed into the SA by 1935 and ceased to exist as an official organization, its ideological legacy and interpersonal networks continued to exert influence in the German conservative-military establishment. By the 1940s, several former Stahlhelm members and sympathizers became disillusioned with Hitler’s dictatorship and were either directly involved in or connected to the July 20, 1944, plot to assassinate the Führer. These included figures within the officer corps who had once aligned with the Stahlhelm’s nationalist, monarchist, and anti-Bolshevik ideals—but who increasingly saw Hitler’s war as a betrayal of the Germany they had once fought to defend. Historian Peter Hoffmann notes that “several of the July 20 conspirators had roots in Stahlhelm or Stahlhelm-adjacent circles, especially among those who had supported Duesterberg’s nationalist-conservative opposition to Hitler in the early 1930s.”[26]

One prominent example is General Friedrich Olbricht, a central figure in the military resistance and organizer of Operation Valkyrie, who was reportedly influenced by traditional conservative-nationalist values, similar to those fostered in Der Stahlhelm circles. Likewise, Carl Goerdeler, the former mayor of Leipzig and a leading civilian in the conspiracy, had long-standing ties to monarchist and Stahlhelm-adjacent networks. Though not acting on behalf of Der Stahlhelm per se, these men embodied the disillusionment of the old nationalist right, whose commitment to German honor and military professionalism stood in stark contrast to Hitler’s radicalism. As Hans Mommsen writes, “the conservative resistance, rooted in aristocratic and nationalist traditions, was the last echo of the pre-Nazi right—among them former Stahlhelm supporters who had never fully accepted the Nazi seizure of power.”[27]

Postwar association

[edit]After its absorption into the Nazi SA in 1934 and formal dissolution by 1935, Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten ceased to exist as an autonomous force. However, its ideological legacy persisted in postwar West Germany through a mixture of veterans' associations, symbolic revival efforts, and eventually far-right extremist activism. In 1951, the group was re-founded in Cologne as a registered association under the name Der Stahlhelm e.V., with Field Marshal Albert Kesselring—a former Wehrmacht officer—serving as honorary patron. Initially recognized by members of Konrad Adenauer’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) as part of a broader anti-Communist Cold War coalition, the group was tolerated for a time despite its nationalist overtones.[28] Yet by the late 1950s, the association began organizing in a paramilitary fashion, donning uniforms at rallies and reviving the militant ethos of its interwar predecessor. As historian Hans-Gerd Jaschke notes, “mainstream political support evaporated as Stahlhelm meetings became militarized and increasingly provocative.”[29] Many events were banned by authorities, and the group lost much of its legitimacy in public life.

By the 1960s and 1970s, Der Stahlhelm e.V. had evolved into a right-wing extremist association, aligning itself with nationalist political parties such as the Deutsche Volksunion (DVU) and the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD).[30] Its symbolic capital, once tied to war commemoration and traditional nationalism, was now embedded in a militant, anti-democratic subculture. In the 1980s, many of its members joined the Wehrsportgruppe Hoffmann, a banned neo-Nazi paramilitary organization, reflecting a further radicalization of the group’s base.[31] The organization became infamous for its association with weapons caches, criminal investigations, and protests against the Wehrmacht exhibition, which documented war crimes committed by the German army.[32] Public scrutiny and internal disarray culminated in the self-dissolution of the Jork branch—the group’s central training center in Lower Saxony—in the year 2000, effectively marking the end of the modern Stahlhelm movement.[33]

Despite its postwar decline, Der Stahlhelm's cultural and ideological legacy—rooted in militarism, ethnic nationalism, and authoritarian values—remained influential in shaping segments of the West German far right. Its attempt to reclaim a sense of national honor after 1945 failed to reconcile with the democratic norms of the Federal Republic, ultimately relegating it to the fringes of German political life.[34]

Ideology

[edit]German nationalism

[edit]The nationalism[35] of Der Stahlhelm was rooted in German militarism,[36][37] monarchism,[38][39] and a desire to reverse the perceived humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles. Seeing itself as the “true guardian of German honor after the disgrace of Versailles”, it “held fast to a vision of a unified, powerful Germany, untainted by defeat and republicanism".[40] The emphasis in the ranks was on unity, sacrifice, and loyalty to a mythologized German past. Rallies, uniforms, and symbols glorified the memory of World War I as a national crucible.[41]

Eastern expansion

[edit]Der Stahlhelm also supported territorial expansion into Eastern Europe, reflecting both revanchist ambitions and older imperial ideas of German colonialism. The organization was committed to overturning the Treaty of Versailles and restoring German sovereignty over lost territories such as East Prussia, Posen, and Silesia. Heinrich August Winkler emphasizes that “members openly called for the reoccupation of the Polish Corridor and the reassertion of German influence in East Prussia and beyond.”[42] This vision extended beyond mere revisionism. Der Stahlhelm also embraced the Drang nach Osten (lit. 'push to the East') as part of a broader historical mission.

As Evans writes, they “championed the idea of Drang nach Osten… aligning with broader nationalist fantasies of colonizing Eastern Europe and reversing the defeat of 1918.”[43] Waite notes that in Stahlhelm speeches and parades, the East was portrayed as “a field for future German colonization,” tying national rebirth to expansionist ambition.[44] These ideas were not yet racialized in the same way as Nazi Lebensraum, but they laid ideological groundwork for it by portraying Eastern Europe as Germany’s rightful sphere of influence.

Authoritarianism and monarchism

[edit]Politically, Der Stahlhelm supported a return to monarchism and authoritarian rule. Its members despised parliamentary democracy, which they viewed as weak, divisive, and alien to German traditions. The group idealized the Kaiserreich and aimed to restore a strong, centralized state under authoritarian leadership. Detlev Peukert describes how the organization “worked to reintegrate national pride through militarized rituals and symbolic defiance of the Republic”,[45] while David Orlow writes that it “stood ideologically to the right of the DNVP and was fiercely anti-democratic, its members idealizing the Kaiserreich and opposing all forms of parliamentary politics.”[46] While the group’s immediate aim was the creation of a “strong presidential regime or an authoritarian substitute for democracy”,[47] Der Stahlhelm supported the idea of reestablishing a hereditary monarchy as a stabilizing force. In setting themselves apart from Hitler's National Socialist movement as "German fascists", leaders of the veterans association identified with the Mussolini regime in Rome that had accommodated the Italian monarchy.[48]

"Third way" economics

[edit]Economically, Der Stahlhelm rejected both Marxist socialism and unregulated capitalism,[49] preferring instead a nationalist corporatist model. It advocated for the protection of the German Mittelstand (middle class) and sought an economy insulated from both foreign capital and internal class struggle. As Orlow notes, the group “supported a form of economic nationalism that opposed both Marxist collectivism and international capitalism, favoring instead the protection of small property and the restoration of the Mittelstand”.[50] Its members frequently voiced support for rural traditions and economic autarky, seeing national self-sufficiency as the only path to recovery from inflation, unemployment, and dependency on foreign loans.[51] Theodor Duesterberg, deputy leader of Der Stahlhelm, bluntly summarized the organization’s position: “The German economy must belong to the German people—not to the speculators in New York or the Marxists in Berlin.”.[52]

Protestant religious identity

[edit]Religious identity also played a formative role in Der Stahlhelm’s ideology. Although not a confessional group, it drew heavily on Protestant nationalist traditions, particularly Lutheran values of obedience, duty, and divine order. Marked by cultural Protestantism rather than theological depth, the group used Christianity as a moral counterweight to Weimar secularism, Bolshevism, and liberal modernity. Richard Evans writes that Der Stahlhelm “drew heavily on Protestant nationalist imagery, cultivating a narrative of sacrifice, moral order, and German unity blessed by divine providence.”[53] Similarly, Peukert observes that “traditional Christian values… were integral to Der Stahlhelm’s self-image,” as it portrayed itself as “a moral force grounded in faith, duty, and sacrifice.”[54] Steigmann-Gall confirms that Der Stahlhelm’s leadership “frequently invoked Christianity in public statements,” portraying the organization “as a Christian bulwark against both atheistic Bolshevism and liberal decadence.”[55] These religious values further reinforced the group’s claim to be a spiritual as well as national redeemer of Germany.

Class collaboration

[edit]Der Stahlhelm promoted a vision of class collaboration grounded in nationalism and militarized solidarity rather than in social justice or worker empowerment. Central to this worldview was the ideal of the Frontgemeinschaft—the notion that the trenches of World War I had forged a unique sense of unity among soldiers regardless of social background. This myth was applied to civilian life as a model for a harmonious national community, in which class divisions would be subordinated to collective duty, obedience, and patriotic purpose. As George L. Mosse writes, “The comradeship of the front became a symbol of national regeneration, one that ignored class conflict in favor of an organic, hierarchical unity.”[56] In Stahlhelm ideology, workers and employers alike were expected to serve the nation under the guidance of a strong state, mirroring the discipline and order of the military. While this resembled fascist models of corporatism, it was less systematic than Italian fascist syndicalism or Nazi corporative structures. Instead, it reflected a reactionary conservatism that saw class harmony as possible only under authoritarian leadership and national revival. Richard J. Evans notes that “veteran groups like Der Stahlhelm valorized sacrifice and discipline, portraying class struggle as a dangerous form of division and undermining the nation’s unity.”[57]

Anti-Polish sentiment

[edit]Der Stahlhelm harbored strong anti-Polish sentiment, reflective of wider right-wing nationalist ideologies that viewed Poland as an illegitimate state occupying historically German lands, particularly in Silesia and the Polish Corridor. As historian Robert G. L. Waite notes, “Der Stahlhelm was among the most vocal in opposing any recognition of Poland’s territorial gains, portraying the Polish state as a threat to German unity and culture.”[58] Anti-Polish rhetoric was often couched in racialized language, portraying Poles as "culturally inferior" and unfit to govern former German territories.[59] Historian Richard Blanke notes that Der Stahlhelm’s publications “echoed long-standing German stereotypes of Poles as backward and uncivilized” and often framed the Polish presence in former Prussian territories as a threat to German national identity and territorial integrity.[60] Der Stahlhelm’s anti-Polish stance helped legitimize revanchist demands for territorial revision and aligned with broader völkisch ideologies that would later become central to Nazi expansionist goals.

Antisemitism

[edit]Antisemitism was not uniformly doctrinal in Der Stahlhelm’s early years, but it became more pronounced over time, especially under Duesterberg, who was associated with völkisch-nationalist elements. The group adopted traditional antisemitic tropes linking Jews to Marxism, finance, and the supposed cultural degeneration of Weimar. Robert G. L. Waite explains that Der Stahlhelm leaders and members “frequently expressed resentment of Jewish financiers and industrialists whom they blamed for Germany’s defeat and economic collapse.”[61] During the 1932 German presidential elections, Duesterberg ran against Hitler as the candidate of the nationalist right, but his campaign collapsed when Nazi propaganda revealed his partial Jewish ancestry—ironically demonstrating how antisemitism had become an entrenched weapon in nationalist politics, even among former allies.[62] After Hitler came to power, Der Stahlhelm was gradually absorbed into the Nazi paramilitary structure, and its anti-Semitic elements were folded into the broader racial ideology of National Socialism.[63]

In summary, Der Stahlhelm’s ideological foundation rested on reactionary nationalism, a call for military and moral renewal, and a rejection of both leftist and liberal democratic values. Economically, it sought a nationalist “third way,” grounded in tradition, small business, and national sovereignty. While its antisemitism was not always explicit, it became increasingly evident in the group's rhetoric and affiliations, ultimately paving the way for its alignment with the Nazi regime.

Theoretical framework

[edit]The ideological function of Der Stahlhelm can be best understood within the dual framework of veteran myth-making and the Conservative Revolution. Drawing heavily on the memory of World War I, Der Stahlhelm mobilized a powerful frontline myth—the belief that veterans embodied a unique moral authority, forged in sacrifice and comradeship, which entitled them to shape the nation’s future. Detlev Peukert writes, the group constructed “a vision of national salvation… forged out of the trauma of war,” where the legitimate political subject was the front soldier, not the parliamentary citizen.[64] This sacralization of the war experience allowed Der Stahlhelm to claim an anti-democratic form of legitimacy rooted not in law, but in blood and suffering. At the same time, Der Stahlhelm must be situated within the broader ideological current of the Conservative Revolution—a loose alliance of nationalist, anti-modernist thinkers and movements that sought to dismantle Weimar liberalism while rejecting Marxism and mass democracy. The group operated as the extraparliamentary arm of the German National People’s Party (DNVP), providing paramilitary muscle and street mobilization for a coalition of monarchists, völkisch ideologues, and reactionary elites. David Orlow notes that Der Stahlhelm “served as an extraparliamentary extension of the DNVP, providing muscle and street presence that formal conservatives could not offer directly.”[65] Through this dual lens of combat myth and counter-revolutionary alliance, Der Stahlhelm emerges not simply as a veterans’ group but as a key cultural and political force in the fragmentation of the Weimar Republic.

Conservative Revolution

[edit]Although not a formal part of the Conservative Revolutionary intellectual movement, Der Stahlhelm reflected its central ideas—militant nationalism, anti-democracy, and the longing for a völkisch national rebirth. George L. Mosse characterizes Der Stahlhelm as a mass-based nationalist organization that “expressed many of the ideals of the Conservative Revolution—its nationalism, militarism, and the longing for a rebirth of the German Volk.”[66] This ideological overlap was especially evident in the Stahlhelm’s opposition to the Weimar Republic and its celebration of the Frontgemeinschaft (front-line camaraderie), which they sought to transpose into a new political and social order. Robert G. L. Waite also notes that although Der Stahlhelm initially kept some distance from Nazism, it nonetheless “shared with the Conservative Revolutionaries a desire to destroy Weimar democracy and replace it with an authoritarian order based on nationalism and military values.”[67] This authoritarian longing connected the group ideologically with thinkers like Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Oswald Spengler. Detlef Mühlberger describes Der Stahlhelm as a “bridging organization, ideologically placed between traditional conservatives and the radical nationalist ideologues of the Conservative Revolution.”[68] This position made Der Stahlhelm both a participant in and a facilitator of broader right-wing radicalization, despite not embracing full-scale fascist revolution. Jeffrey Herf further points to the influence of Conservative Revolutionary thought on Der Stahlhelm’s leadership, noting that figures like Franz Seldte “drew on ideas circulating within the Conservative Revolution, especially a rejection of Weimar liberalism and a call for a militarized national community.”[69] Aristotle Kallis similarly writes that while Der Stahlhelm “did not advocate fascism per se, it served as an ideological incubator for notions of ethnic nationalism, anti-parliamentarianism, and national rebirth—central to the Conservative Revolutionary worldview.”[70]

Frontgemeinschaft

[edit]A central pillar of Der Stahlhelm’s ideological identity was the glorification of the Frontgemeinschaft, or frontline comradeship, which veterans had experienced in the trenches of World War I. This concept served not only as a nostalgic memory but as a political and social ideal, which Der Stahlhelm sought to project onto the entire German nation. The Frontgemeinschaft was imagined as a pure, heroic community—bound by loyalty, sacrifice, discipline, and unity—that stood in stark contrast to the fragmented, pluralistic, and democratic society of the Weimar Republic. As George L. Mosse explains, “The front line was considered the cradle of the new nation. The comradeship of the trenches was seen as the authentic national community—free of class division, ideological conflict, and internal enemies.”[71] Der Stahlhelm adopted this ideal as a model for a new Volksgemeinschaft, a racially and ideologically homogenous national community, rooted in martial values and authoritarian hierarchy. Richard Bessel similarly notes that “veterans’ organizations such as Der Stahlhelm invoked the memory of trench comradeship to argue for a regenerated Germany based on discipline, obedience, and sacrifice.”[72] This mythologized version of the war experience legitimized their anti-democratic worldview, allowing them to present themselves as the true heirs of the national struggle and moral compass of the postwar state.

Traditional masculine identity

[edit]Der Stahlhelm was built on a specific model of masculine identity: the front soldier (Frontkämpfer) who had proved his worth in the trenches through endurance, sacrifice, and loyalty. This masculine archetype became a template for the ideal national citizen, and its values—discipline, obedience, physical toughness, and readiness to sacrifice for the Fatherland—were elevated as the moral foundation of postwar society. As George L. Mosse explains, Der Stahlhelm and similar groups “turned the war experience into a rite of passage that separated true men—defined by courage, endurance, and honor—from effeminate civilians, Jews, pacifists, and socialists.”[73]

This form of reactionary masculinity stood in direct opposition to the perceived softness, decadence, and moral relativism of Weimar liberalism. Men were expected to serve as defenders of national unity, tradition, and hierarchy, while women were entirely excluded from political life in Der Stahlhelm’s worldview. The movement upheld the gender ideals of the völkisch right, celebrating women primarily as mothers of soldiers, guardians of domestic purity, and symbolic bearers of racial continuity. Public roles for women, especially in politics, journalism, or cultural life, were seen as symptoms of a society in decay.

The group's ceremonies, uniforms, insignia, and iconography further reinforced a militarized male bond. Events were filled with military salutes, speeches on duty and sacrifice, and the invocation of dead comrades—rituals that blurred the line between remembrance and political mobilization. These performances created what cultural historian Klaus Theweleit describes as “a brotherhood of steel”—an emotional and political identity rooted in male collectivity and violence.[74] This collective identity was more than symbolic: it produced a social network of masculinity that excluded outsiders, rejected pluralism, and sought a return to an idealized, patriarchal national order.

Even after its formal dissolution, the masculine ideal constructed by Der Stahlhelm persisted in the culture of postwar far-right movements and found echoes in later paramilitary youth training, the rhetoric of the NPD, and neo-fascist nostalgia. The fusion of gender, nationalism, and militarism made Der Stahlhelm not just a political actor but a cultural force, shaping how the nationalist right defined the German man and, by contrast, who was unworthy of belonging to the nation.

Influence outside Germany

[edit]Although Der Stahlhelm was fundamentally a German veterans’ organization, its symbolism and ideological framework had a notable impact on German-speaking fascist movements in Austria and Czechoslovakia during the interwar period. In both countries, large ethnic German populations—suddenly minorities after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—found in Stahlhelm-style organizations a model for asserting their cultural and political identity. In Austria, veterans’ groups like the Frontkämpfervereinigung and the Heimwehr adopted the language of the Frontgemeinschaft and the imagery of the steel helmet, promoting a blend of militarism, ethnic nationalism, and anti-Marxism that paralleled the German Stahlhelm. Historian Robert O. Paxton notes that “the appeal of the frontline myth spread across German-speaking Europe, and Stahlhelm-style organizations in Austria adopted its symbolism almost without modification.”[75]

In Czechoslovakia, similar ideas took root in the Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront (later the Sudeten German Party), where ethnic German veterans romanticized their wartime service and used the imagery of Der Stahlhelm to assert a nationalist identity in opposition to the Czech-dominated state. The notion of a unified, disciplined Volksgemeinschaft grounded in wartime solidarity was deeply attractive to Sudeten Germans who rejected liberal democracy and sought reintegration with the German Reich. As George L. Mosse observes, “The Stahlhelm ideal of a national community forged through war and struggle had international appeal, particularly among the displaced and resentful German minorities in the successor states.”[76] The influence of Der Stahlhelm was thus not confined to Germany itself but helped export a militarized, ethnic nationalist ideology that fed directly into the Pan-German and fascist movements of the 1930s. It provided not just aesthetic inspiration—in its uniforms, insignia, and rituals—but also an organizational model of how veterans could be mobilized for political purposes. In this way, Der Stahlhelm played a transnational role in shaping right-wing extremism in post-Habsburg Central Europe.

Political decline and tactical limitations

[edit]

Despite its massive membership and national reach, Der Stahlhelm ultimately failed to convert its symbolic power into lasting political influence, particularly when compared to the revolutionary success of the NSDAP. While the Nazis offered a forward-looking, albeit apocalyptic, vision of racial rebirth and societal transformation, Der Stahlhelm remained firmly rooted in monarchist nostalgia and Wilhelmine tradition. Its appeal was strongest among conservative veterans, landowners, and segments of the middle class, but it lacked resonance among the working class and rural poor, who increasingly gravitated toward the populist rhetoric and social agitation of Hitler’s movement. The organization’s leadership, clinging to outdated imperial loyalties, was unable to articulate a compelling alternative to Weimar democracy beyond vague calls for national honor and restored hierarchy. David Orlow writes: “The Stahlhelm looked backward to the Kaiserreich rather than offering a future-oriented vision like the Nazis. Its inability to evolve made absorption into the SA inevitable.”[77] Rather than seizing revolutionary opportunity, Der Stahlhelm relied on ceremony, hierarchy, and symbolism, which proved inadequate in the face of the NSDAP’s dynamic mass mobilization and totalitarian ambition.

Published works

[edit]

Several members and affiliates of Der Stahlhelm produced written works that articulated the organization's nationalist and militarist ideology during the Weimar Republic. These publications, though not typically philosophical in nature, combined memoir, political commentary, and ideological affirmation to promote a vision rooted in anti-democracy, national renewal, and front-line camaraderie.

Franz Seldte, co-founder and long-time leader of Der Stahlhelm, published a trilogy titled Der Vater aller Dinge, which included M.G.K. (1929), Dauerfeuer (1930), and Vor und hinter den Kulissen (1931). These volumes blended Seldte’s war memoirs with political reflections, emphasizing military virtues such as discipline, sacrifice, and national loyalty. In M.G.K., Seldte declared that "Der Stahlhelm ist nicht nur ein Bund der Frontsoldaten, sondern eine Bewegung, die das Erbe des Frontgeistes in das politische Leben der Nation trägt" ("Der Stahlhelm is not merely a federation of front-line soldiers, but a movement that carries the spirit of the front into the political life of the nation").[78]

Theodor Duesterberg, Seldte’s deputy and later presidential candidate in 1932, attempted to frame the organization’s legacy in a more moderate light after World War II. In Der Stahlhelm und Hitler (1949), Duesterberg portrayed himself as a critic of National Socialism, writing, "Ich habe stets davor gewarnt, den Stahlhelm in die Nähe der Nationalsozialisten zu bringen" ("I always warned against bringing Der Stahlhelm close to the National Socialists").[79] However, historians have questioned this portrayal, noting the organization's early cooperation with right-wing nationalist movements, including the Nazi Party.

Wilhelm Kleinau, another prominent figure within Der Stahlhelm, contributed significantly to its intellectual output. As editor of the Stahlhelm-Jahrbuch and co-editor of Die Standarte, he promoted the group’s ideals through journalistic and commemorative publications. In Soldaten der Nation (1933), Kleinau wrote, "Die Frontsoldaten sind berufen, das neue Deutschland zu führen, gestählt durch den Krieg, bereit für die nationale Erneuerung" ("The front-line soldiers are called to lead the new Germany, tempered by war, ready for national renewal").[80] Together, these writings reveal the ideological convictions of Der Stahlhelm's leadership and their belief in the soldier as a model citizen who could restore Germany’s strength after the perceived humiliation of Versailles and the instability of the Weimar Republic. While often overshadowed by the more radical rhetoric of the Nazis, Der Stahlhelm’s literature reflects a coherent vision of militarist conservatism and veteran-led nationalism.

Cultural commemoration

[edit]

After Germany’s defeat in 1918 and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the cultural landscape of the Weimar Republic was saturated with trauma, shame, and loss. Der Stahlhelm emerged into this environment not just as a gathering point for veterans, but as a custodian of nationalist memory. The group played a leading role in shaping how the war dead were remembered—not as victims of military failure, but as martyrs betrayed by politicians, leftists, and Jews. Their memorial ceremonies, marches, and cemetery rituals did not simply mourn the dead; they accused the living—particularly the democratic leadership—of treason.

As George L. Mosse argues, “Stahlhelm events transformed mourning into a form of political mobilization. The dead of the Great War were invoked as silent witnesses against the Republic.”[81] This framing allowed Der Stahlhelm to claim moral authority over the national future by monopolizing the memory of the wartime past. The ritualization of grief—through speeches, music, grave-site ceremonies, and the public display of steel helmets and imperial flags—became a performative rejection of Weimar values, a way of restaging the war in symbolic terms to continue the struggle on political and cultural fronts. These commemorative activities often had the structure of quasi-religious ceremonies. The war dead were sanctified, their sacrifice mythologized, and their memory used to call for renewed national struggle. According to historian Jay Winter, such commemorative practices created what he calls a “sacred canopy” over nationalist movements, allowing groups like Der Stahlhelm to translate political objectives into moral obligations rooted in collective suffering. [82]

These rituals also served a mobilizing and exclusionary function. To participate in Der Stahlhelm’s vision of national mourning was to accept a particular reading of the war—one that excluded Weimar liberals, pacifists, socialists, and Jews from the national narrative. The myth of the "stab in the back" (Dolchstoßlegende) was regularly invoked at these gatherings, reinforcing the idea that Germany’s internal enemies had sabotaged the army’s otherwise noble efforts. Thus, Der Stahlhelm’s commemorative culture was not merely backwards-looking—it was forward-directed, shaping nationalist identity, legitimising political violence, and laying the emotional groundwork for an authoritarian revival.

Impact of Italian fascism

[edit]Though Der Stahlhelm emerged independently from Italian fascism, it was deeply influenced by the example of Mussolini’s seizure of power in 1922, which many German nationalists admired as a successful model of postwar regeneration through militarism, discipline, and authoritarian rule. Italian Fascism offered Der Stahlhelm a blueprint for how a veterans’ movement could evolve into a mass political force capable of undermining democratic institutions and establishing a new nationalist order. The organization was particularly inspired by the aesthetic and organizational innovations of the Fascist movement, including the use of uniforms, parades, nationalist rituals, and a myth of heroic sacrifice. Mosse writes, “German nationalist organizations such as Der Stahlhelm found in Mussolini’s Italy a model of how the comradeship of the trenches could be transformed into a political system based on order, hierarchy, and myth.”[83]

Political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset has examined the class basis of right-wing extremist politics in the 1920–1960 era. He reports:

"Conservative or rightist extremist movements have arisen at different periods in modern history, ranging from the Horthyites in Hungary, the Christian Social Party of Dollfuss in Austria, Der Stahlhelm and other nationalists in pre-Hitler Germany, and Salazar in Portugal, to the pre-1966 Gaullist movements and the monarchists in contemporary France and Italy. The right extremists are conservative, not revolutionary. They seek to change political institutions in order to preserve or restore cultural and economic ones, while extremists of the centre [fascists/Nazis] and left [communists/anarchists] seek to use political means for cultural and social revolution. The ideal of the right extremist is not a totalitarian ruler, but a monarch, or a traditionalist who acts like one. Many such movements in Spain, Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Italy have been explicitly monarchist […] The supporters of these movements differ from those of the centrists, tending to be wealthier, and more religious, which is more important in terms of a potential for mass support."[84]

Despite its more conservative and monarchist roots, Der Stahlhelm increasingly echoed Fascist themes of national rebirth, anti-parliamentarianism, and anti-communism in the 1920s. While it did not embrace a revolutionary ideology to the same extent as the Nazis or Italian Fascists, it saw itself as part of a transnational right-wing resurgence that rejected liberalism and socialism alike. Historian Stanley G. Payne notes that “the example of Fascist Italy encouraged German nationalist paramilitary groups to believe that an authoritarian revolution led by veterans was not only possible but necessary.”[85] The March on Rome was closely studied in Stahlhelm circles, and some leaders openly discussed the potential for a similar nationalist coup in Germany, especially during the years of hyperinflation and democratic instability.

However, Der Stahlhelm remained less revolutionary than Mussolini's Fascists or Hitler’s Nazis. It lacked a singular charismatic leader, and its ideological center remained loyal to the conservative establishment rather than forging a new political class. Nevertheless, the rhetorical and symbolic influence of Italian Fascism helped shift Der Stahlhelm’s focus from purely commemorative activities toward more direct political mobilization, ultimately setting the stage for its alliance with radical right forces in the late Weimar era.

Relationship with Nazism

[edit]Although Der Stahlhelm and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) shared several ideological elements, including militant nationalism, antisemitism, and rejection of Weimar democracy, they diverged significantly in their origins, worldviews, and political methods. Der Stahlhelm was rooted in the Wilhelmine tradition and monarchist values. It aimed to restore the old imperial order and opposed revolutionary change. As Detlev Peukert writes, the Stahlhelm “saw itself as a bulwark of national honor, advocating a return to the values of the Kaiserreich and opposing both socialism and liberal democracy.”[86] The NSDAP, by contrast, was founded in 1920 and pursued a radical, totalizing, racial-nationalist revolution. Richard Evans emphasizes that “while Der Stahlhelm looked backward to an imagined imperial past, the Nazis looked forward to a racial utopia achieved through revolution.”[87]

Leadership and organizational culture further distinguished the two groups. Der Stahlhelm followed a rigid, military-style hierarchy under figures like Seldte and Duesterberg, whereas the NSDAP was built around the Führerprinzip—complete submission to Adolf Hitler. David Orlow notes that “Der Stahlhelm was authoritarian in structure, but not totalitarian in ambition,” whereas “the NSDAP was defined by its revolutionary racial ideology and centralized cult of leadership.”[88] Although both groups were antisemitic, Der Stahlhelm’s antisemitism was more cultural and political, whereas the NSDAP embraced a biological racism that culminated in genocidal policy. George L. Mosse explains that “the Stahlhelm identified Jews as symbols of Weimar decay, but it lacked the radical racial doctrine that defined Nazism.”[89]

Tactically, the NSDAP also distinguished itself through its willingness to embrace both electoral participation and street violence, using its paramilitary wings—the SA and SS—to intimidate opponents and stage rallies that mobilized the masses. Der Stahlhelm, while paramilitary in form, preferred traditional legal channels and aligned itself with the German National People’s Party (DNVP).[90] Ultimately, after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Der Stahlhelm was gradually absorbed into the SA, losing its autonomy and being formally dissolved by 1935. As Evans observes, “Der Stahlhelm’s ideology overlapped enough with Nazism that its destruction was not a rupture, but a natural absorption into the new regime.”[91]

In terms of territorial ambition, both Der Stahlhelm and the NSDAP supported expansion into Eastern Europe, but their justifications and intensity differed. Der Stahlhelm framed its territorial demands primarily in revanchist and nationalist terms, focusing on the reversal of the Treaty of Versailles and the reoccupation of lost territories such as the Polish Corridor and Silesia. As Heinrich August Winkler notes, Der Stahlhelm “openly called for the reoccupation of the Polish Corridor and the reassertion of German influence in East Prussia and beyond.”[92] The NSDAP, however, advanced a far more radical program of racial-imperialist expansion, demanding Lebensraum (lit. 'living space') in Eastern Europe to secure the survival of the Aryan race. This was not merely about borders, but about displacing and exterminating entire populations, a notion absent from Stahlhelm rhetoric.[93]

The two groups also diverged in their approach to mass mobilization. Der Stahlhelm operated within the limits of bourgeois conservatism, organizing veterans through hierarchical discipline and emphasizing ritual, order, and honor. It lacked the emotional dynamism and theatrical appeal that characterized Nazi political culture. As George L. Mosse observes, “Stahlhelm rallies were commemorative; Nazi rallies were transformative, drawing the masses into a vision of rebirth and redemption.”[94] The NSDAP deliberately fostered a populist movement, using propaganda, spectacle, and paramilitary force to mobilize millions across social classes in a totalizing way.

Finally, their religious identities reveal further divergence. Der Stahlhelm was culturally Protestant and embraced a form of conservative Christian nationalism, aligning Lutheran values with German identity. Richard Steigmann-Gall notes that Stahlhelm rhetoric “fused nationalism with a cultural Christianity that was ethnically coded—Christianity was portrayed as the faith of the German Volk.”[95] The NSDAP, by contrast, held a much more ambiguous and instrumental view of religion. While some Nazis like Hitler used Christian language, the party increasingly subordinated religion to its racial worldview. As Evans explains, “Nazism replaced traditional Christianity with a new faith centered on race, struggle, and the Führer.”[96] Thus, while Der Stahlhelm saw itself as defending traditional moral and spiritual values, the NSDAP aimed to reshape German belief systems around a racial-national mythos.

Membership

[edit]During the Weimar Republic, Der Stahlhelm grew rapidly to become one of the largest nationalist paramilitary organizations in Germany. By 1925, it had grown to approximately 500,000 members. This number continued to climb during the late 1920s, and by 1930, the organization reportedly had over 500,000–600,000 members, making it the largest veterans' association in Germany at the time.[97] This massive growth reflected the widespread appeal of its ultranationalist and anti-republican messaging among conservative and disaffected veterans. However, membership began to decline after the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, particularly following the forced integration of Der Stahlhelm into the SA and its eventual dissolution by 1935.

In the postwar period, the reestablished Der Stahlhelm e.V. never came close to regaining its former size. While exact figures are not always disclosed, expert analysis suggest that the organization experienced a steady decline in membership throughout the 1960s and 70s, with further attrition through the 1980s and 1990s, until its formal dissolution in 2000 due to internal decline and pressure from German federal authorities.[98]

Prominent members

[edit]Listed here are some of the most prominent members of Der Stahlhelm throughout its entire existence:

Racial purity crisis

[edit]

In the 1932 German presidential election, Der Stahlhelm nominated Deputy Federal Leader Theodor Duesterberg as their candidate. However, the campaign was quickly overshadowed by a scandal that exposed Duesterberg's partial Jewish ancestry, which became politically devastating in the context of a deeply antisemitic and increasingly radicalized right-wing political climate.

Following this revelation, support for Duesterberg collapsed. His Jewish heritage made him a target of the Nazi Party’s propaganda, which capitalized on racial purity narratives. Joseph Goebbels, among others, amplified the accusations to discredit Duesterberg and Der Stahlhelm as racially impure. This severely damaged Duesterberg’s standing with nationalist and völkisch (ethno-nationalist) voters who viewed Jewish ancestry as incompatible with German national identity. He performed poorly in the first round of voting. Subsequently, he withdrew from the runoff, leaving the field open to the two main contenders: incumbent President Paul von Hindenburg and Adolf Hitler.

In an effort to preserve the group's credibility and align more closely with the dominant racial ideologies of the far-right, Der Stahlhelm responded by radically altering its membership requirements. The changes aimed to eliminate any ambiguity about members' racial purity and loyalty to völkisch ideals. According to historian Wolfram Wette, the proposed reforms included the following conditions:[109][110]

1. Racial Proof through Church Records: Members were required to provide notarized copies of church records confirming that their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were not of Jewish descent. This requirement echoed the Nazi concept of the Ariernachweis (Aryan certificate), which was later codified into Nazi racial laws.

2. Oath of Separation from Jews: Members had to swear, on their word of honor, that they had never engaged in personal, familial, or business relations with Jews in any capacity. This reinforced a strict segregationist and exclusionary policy, aligning with antisemitic purity doctrines.

3. Proof of Ancestral Military Service: Members were also expected to prove that their ancestors had fought in the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon or in the German Wars of Unification. This requirement tied one’s legitimacy in the organization to nationalist military heritage and historical service to the German nation.

4. Proof of World War I Participation: Lastly, individuals had to demonstrate that they themselves had served in World War I, detailing their rank and role. This continued the organization’s founding ethos as a veterans’ league tied to notions of military honor and national sacrifice.

These revised membership criteria not only sought to exclude Jews and those connected to Jews but also to root the organization more deeply in a mythologized, racially pure vision of German history and nationalism. It was a clear attempt to distance Der Stahlhelm from the controversy and to realign it with the racial and ideological currents that were dominating the far-right, particularly those of the rapidly ascending Nazi Party. This episode is significant as it illustrates both the extent of antisemitism in Weimar Germany and how veterans’ organizations like Der Stahlhelm increasingly adapted to Nazi racial ideology in order to maintain relevance and political survival in a radicalizing nationalist landscape.

Regional administration

[edit]Structurally, Der Stahlhelm was organized federally, with substantial autonomy granted to regional and local branches (Gauverbände). While this helped the organization achieve wide geographic reach, especially in Protestant northern and eastern Germany, it also resulted in ideological and tactical divergence between local chapters. In some regions, Der Stahlhelm aligned closely with the German National People’s Party (DNVP), adopting a conservative-monarchist line and collaborating in electoral strategies. In other areas, particularly where economic or political instability was more acute, local Stahlhelm leaders veered toward more radical völkisch or even proto-fascist positions, sympathizing with elements of the NSDAP or adopting anti-Semitic and revolutionary rhetoric.

Dennis Werberg emphasizes this point, noting that “The Stahlhelm lacked a coherent national leadership and suffered from deep internal rifts, particularly between pragmatic conservatives and völkisch radicals.” [111] These ideological schisms became particularly evident during critical national events, such as the 1932 German presidential election, when Stahlhelm leadership (under Theodor Duesterberg) launched a campaign in opposition to Hitler, but failed to unite the organization behind it due to conflicting loyalties at the grassroots level. This fragmentation was not just political—it was also cultural and generational. Older members often clung to Kaiserreich-era loyalties, focusing on monarchical restoration, while younger or more radical members were drawn to the revolutionary fervor and anti-Weimar rhetoric of the Nazi movement. As Richard Bessel notes, “while the national leadership attempted to steer a conservative course, it could not prevent many younger members from being drawn to the more dynamic and brutal appeal of the SA.”[112]

This internal disunity severely weakened Der Stahlhelm’s ability to act as a cohesive political force, especially in the face of the NSDAP’s centralized, charismatic, and disciplined structure. Unlike the Nazis, who emphasized total ideological alignment and organizational loyalty, Der Stahlhelm tolerated a broad range of nationalist perspectives—an openness that, while initially attractive to many disillusioned veterans, ultimately left it vulnerable to co-optation and marginalization. By 1933, when Franz Seldte surrendered the organization to the Nazi regime and pledged loyalty to Hitler, the internal contradictions of Der Stahlhelm were fully exposed. What had once been envisioned as an autonomous pillar of the nationalist right was now dissolved piecemeal, with more radical elements absorbed into the SA and others retreating from political life. The organization’s regionalism, once a strength in its grassroots expansion, had become a fatal weakness in an era demanding ideological and strategic unity.

Command structure

[edit]Top leadership

[edit]

At its core, Der Stahlhelm was governed by a central leadership body known as the Führungsstab (Leadership Staff). This department, directed by the Bundesführer (lit. 'Federal Leader'), initially Franz Seldte and later Theodor Duesterberg, coordinated national strategy, managed communication between local chapters, and led political negotiations, particularly with the German National People's Party (DNVP). The leadership played a pivotal role in aligning the organization with right-wing coalitions, including the Harzburg Front in 1931, which was a bloc formed to oppose the Weimar Republic and included figures such as Hugenberg and Hitler.[113]

Other departments

[edit]Another vital element of Der Stahlhelm was its "Political Department", which managed the group’s engagement in electoral politics and ideological battles. It worked closely with conservative-nationalist parties and served to radicalize the organization’s stance against the democratic institutions of Weimar Germany. The group even participated independently in presidential elections, fielding Duesterberg as a candidate in 1932, although his candidacy faltered due to Nazi attacks on his Jewish ancestry. [114]

To shape public opinion, Der Stahlhelm operated a "Propaganda and Press Department", which oversaw the publication of its official newspaper, Der Stahlhelm. This department was responsible for promoting the group’s core values—militarism, nationalism, anti-communism, and anti-parliamentarianism. The messaging emphasized restoring Germany’s former glory and vilifying both the Treaty of Versailles and the democratic system.[115] Youth mobilization was handled by the Jungstahlhelm, the youth wing founded in 1926. This group provided paramilitary training and ideological education to young German men, preparing them for future integration into the main organization. It served a role similar to that of the Hitler Youth, instilling nationalist ideals at an early age.[116]

Despite being male-dominated, Der Stahlhelm also formed a "Women’s Auxiliary Division", the Stahlhelm-Frauenbund. This wing supported logistical needs, organized events, and promoted conservative gender roles centered on family, loyalty, and patriotism. Women were encouraged to support the men through domestic and organizational roles rather than political activism.[117] Administrative control fell to the "Finance and Administration Department", which managed membership fees, donations (often from industrialists sympathetic to nationalist causes), and internal budgeting. This department ensured the acquisition and distribution of uniforms, flags, and other symbols crucial to maintaining the group’s militant identity.

The "Military Training and Security Department" was responsible for conducting weapons drills, organizing marches, and providing security at public events. Although officially disarmed after the war, many members retained or acquired weapons illegally and were trained in their use. This further blurred the lines between veterans’ group and private militia.[118] Internally, Der Stahlhelm enforced strict discipline through a "Legal Affairs and Internal Discipline" unit. This division resolved disputes within the organization and maintained ideological unity. Given the rise in factionalism within nationalist circles during the late Weimar years, this function was increasingly important to prevent splintering.

Finally, Der Stahlhelm's structure extended nationwide through a decentralized network of Regional and Local Chapters, known as Gaue and Ortsgruppen. These local cells operated semi-independently, organizing marches, rallies, and community outreach while still adhering to directives from the central leadership. This structure enabled the organization to claim hundreds of thousands of members at its peak, making it one of the largest paramilitary forces in interwar Germany.[119] Altogether, Der Stahlhelm’s internal departments made it a militarized organization with wide-reaching influence. While it initially presented itself as a veterans’ advocacy group, its elaborate structure revealed a deeper ambition: to reshape German society along nationalist and authoritarian lines, paving the way for eventual coordination with and absorption into the Nazi regime after 1933.

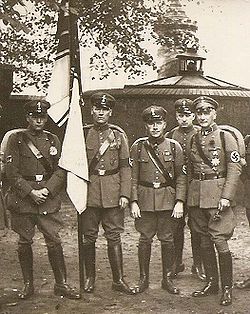

Flag companies

[edit]Within Der Stahlhelm, ceremonial units known as Fahnen- und Ehrenkompanien (lit. 'Flag and Honor Companies') played a significant role in public events and parades. These units were responsible for carrying standards and flags, symbolizing the organization's militaristic and nationalist values. Members of these ceremonial units often wore distinctive insignia, including ornamental gorgets known as Ringkragen. These gorgets were typically semi-circular metal plates worn around the neck, featuring elaborate designs such as the Stahlhelm emblem set within an oak leaf wreath, flanked by detailed standard flags, and topped by a crowned German national eagle clutching a sword and quiver of arrows. The gorgets were suspended from a silvered bronze multi-link neck chain, adding to their ceremonial appearance.

Youth wing

[edit]

The Jungstahlhelm, the youth wing of Der Stahlhelm played a significant role in militarizing German youth during the interwar period. As part of the broader paramilitary movement, the Jungstahlhelm targeted boys between the ages of 14 and 24, offering them a structured, military-style environment intended to instill values of nationalism, discipline, and readiness for eventual service. According to the official records from the Nuremberg Trials, the organization’s youth divisions were formally structured into two primary groups: “The Scharnhorst, which was the Stahlhelm youth organization for boys under 14… and the Wehrstahlhelm, which included the Jungstahlhelm (boys from 14–24 years of age).”[120]

The ideological underpinnings of the Jungstahlhelm were closely tied to Der Stahlhelm’s broader objectives, which included opposing the perceived failures of the Weimar Republic and promoting a revisionist, nationalist agenda. This goal is reflected in both the organization’s propaganda and its public activities. Academic analysis also sheds light on the organization’s paramilitary significance. In a chapter titled “Paramilitary Volunteers for Weimar Germany’s ‘Wehrhaftmachung’,” the Jungstahlhelm is highlighted as a key contributor to the "militarization of society" that occurred as Weimar Germany grappled with post-war instability and the Versailles Treaty’s restrictions on military development. Local chapters, such as the one in Perleberg, were active and visible in public life, reinforcing the perception of the organization as a proto-military force for the youth.[121].

Furthermore, the Jungstahlhelm's operations must be understood within the broader context of Der Stahlhelm’s goals, as outlined in scholarly assessments like those in the NIDS Joint Research Series. The group not only aimed to provide structure and camaraderie to war veterans and their families but also to unite conservative and nationalist forces in opposition to both socialism and parliamentary democracy.[122] Through its militarized rituals, nationalist education, and close alignment with veteran and right-wing political movements, the Jungstahlhelm helped lay the groundwork for the later absorption of such youth organizations into the Nazi Party’s structures, including the Hitler Youth (HJ). It stands as a striking example of how interwar German society used organized youth movements to cultivate political loyalty and prepare the next generation for ideological conformity and conflict.

Ranks and insignia

[edit]Each rank had corresponding insignia, often displayed on the collar or shoulder, to signify the individual's position and responsibilities within the organization.[123]

| Collar insignia | Shoulder insignia | Ranks |

|---|---|---|

|

Bundesführer | |

|

Bundeshauptmann | |

|

Obergruppenführer | |

|

Divisionsführer | |

|

Brigadeführer | |

|

Regimentsführer | |

|

Stabsführer | |

|

Bataillonsführer | |

|

Kompanieführer | |

|

Oberzugführer | |

|

Zugführer | |

|

Oberfeldmeister | |

|

Feldmeister | |

|

Gruppenführer | |

|

Stabswehrmann | |

|

Oberwehrmann | |

|

Wehrmann | |

| Source:[124] |

Leaders

[edit]| No. | Leader (birth–death) |

Portrait | Constituency or title | Took office | Left office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Franz Seldte (1882–1947)

|

|

Federal Leader of Der Stahlhelm | 25 December 1918 | 28 March 1934[c] |

| 2 | Theodor Duesterberg (1875–1950)

|

|

Deputy Federal Leader of Der Stahlhelm | 9 March 1924 | 21 June 1933 |

Election results

[edit]

Federal elections (Reichstag)

[edit]| Date | Votes | Seats | Position | Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ± pp | No. | ± | |||

| March 1933 | 3,136,760 | 7.97[d] | 52 / 648

|

Coalition | |||

Presidential election

[edit]| Election year | Candidate | 1st round | 2nd round | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Rank | Votes | % | Rank | |||

| 1932[e] | Theodor Duesterberg | 2,557,729[128] | 6.79 | 4th | — | Lost | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ From 28 March 1934 to 7 November 1935, the organization was renamed to the Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher frontkämpfer-Bund (Stahlhelm) before being merged into the SA.

- ^ Founded in 1951 in Cologne, Germany. Throughout the mid-20th century, the organization established many regional and local chapters before finally dissolving on June 12, 2000.[15]

- ^ Became Federal Leader of the Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher frontkämpfer-Bund (Stahlhelm) from 28 March 1934 to 7 November 1935.

- ^ Political and electoral alliance of the German National People's Party (DNVP), Der Stahlhelm and the Agricultural League.

- ^ The Harzburg Front was starting to show disunity regarding the election, with the DNVP agreeing to support the Stahlhelm's choice of candidate in exchange for support in state elections.[125] Hugenberg attempted to keep Hitler in line with the Harzburg Front at a meeting on 20 February, but to no avail; at a party rally on 22 February NSDAP member Goebbels revealed that Hitler would run in the race.[125][126] The Stahlhelm's choice – Theodor Duesterberg – was announced later that day, overshadowed by Hitler's candidacy.[127]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Stackelberg (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany, p. 243.

- ^ Evans, R. J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin. p. 141.

“Der Stahlhelm was the largest paramilitary organization in the Weimar Republic. It emphasized honor, sacrifice, and camaraderie among veterans, but its deeper purpose was political: to destabilize the Republic and promote a right-wing authoritarian alternative.”

- ^ The central organ, Der Stahlhelm, was first published as a bi-monthly, and from 1924 as a weekly newspaper. Circulation significantly exceeded 100,000 in the mid-1920s but subsequently fell below that level. In addition to smaller publications for students and monthly letters for Stahlhelm leaders, Die Standarte was published in 1925/26 with the subtitle "Contributions to the Intellectual Deepening of the Front Thought". Unofficial Leader Supplement to the Stahlhelm. It was published from 1926 to 1929, with the addition of Wochenschrift des neuen Nationalismus (Weekly Journal of the New Nationalism) by Ernst Jünger, Franz Schauwecker and others.

- ^ Carsten, F. L. (Ed.). (1987). German nationalism and the European response, 1890–1945. London: Routledge. p. 219.

“The Stahlhelm embraced the idea that the German Volk was a unified ethnic body defined by heritage and loyalty. Their hostility to internationalism and pluralism came from a belief that only ethnic homogeneity could preserve national strength.”

- ^ Orlow, D. (1969). The history of the Nazi Party: 1919–1933. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. p.122.

“Though not biologically racist in the early sense, Der Stahlhelm nonetheless operated with an ethnic-nationalist framework. Its ideal of the Volk excluded Jews, socialists, and modernists from the national body.”

- ^ Orlow, D. (1969). The History of the Nazi Party: 1919–1933. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 121.

“The Stahlhelm supported the return of Germany’s lost eastern territories and expressed open sympathy with Pan-German ideas of eastward expansion, which they considered part of Germany’s natural historical mission.”

- ^ Waite, R. G. L. (1952). Vanguard of Nazism: The Free Corps Movement in Post-War Germany 1918–1923. Harvard University Press. p. 232.

“Like other veterans’ groups, Der Stahlhelm considered itself a bulwark against Bolshevism and the ‘November criminals,’ advocating for a return to strong leadership and traditional values.”

- ^ Winkler, H. A. (2006). Germany: The Long Road West, Volume 1: 1789–1933. Oxford University Press. p. 389.

“For Der Stahlhelm, nationalism was not only a matter of territory or sovereignty, but of restoring an authoritarian state and eradicating the shame of democracy and defeat.”

- ^ Orlow, D. (1969). The History of the Nazi Party: 1919–1933. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 122.

“Der Stahlhelm stood ideologically to the right of the DNVP and was fiercely anti-democratic, its members idealizing the Kaiserreich and opposing all forms of parliamentary politics. [...] Der Stahlhelm stood ideologically to the right of the DNVP and promoted a nationalist revivalism that bordered on fascism: it was ultranationalist in tone, authoritarian in structure, and anti-democratic in purpose.”

- ^ "Stahlhelm-Bundeslied [Bundeslied vom Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten][+Liedtext]" (video). youtube.com. Nils Robin Moser. April 29, 2021.

- ^ Pfleiderer, Doris (2007). "Volksbegehren und Volksentscheid gegen den Youngplan, in: Archivnachrichten 35 / 2007" [Initiative and Referendum against the Young Plan, in: Archived News 35 / 2007] (PDF). Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg (in German). p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Officially called the "Reich Committee for the German People's Initiative against the Young Plan and the War Guilt Lie" (Reichsausschuß für die Deutsche Volksinitiative gegen den Young-Plan und die Kriegsschuldlüge)[11]

- ^ Jones, Larry E. (Oct., 2006). "Nationalists, Nazis, and the Assault against Weimar: Revisiting the Harzburg Rally of October 1931" Archived 26 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. German Studies Review. Vol. 29, No. 3. pp. 483–94. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Fulbrook, M. (1992). The Divided Nation: A History of Germany, 1918–1990. Oxford University Press. p. 62.

“The Stahlhelm actively participated in demonstrations and political violence during the 1920s, often clashing with left-wing militias. Though officially independent, it increasingly functioned as a semi-official militia of the right-wing Nationalist Party.”

- ^ Neofaschistischer »Der Stahlhelm e. V.« hat sich selbst aufgelöst! VVN-BdA Stade 2003. Auf Stade-VVN-BdA.de, abgerufen am 19. Oktober 2019.

- ^ Jones, L. E. (2014). German Right, 1918–1930: Political Parties, Organized Interests, and Patriotic Associations in the Struggle against Weimar Democracy. Cambridge University Press, p. 209

- ^ Peukert, D. J. K. (1991). The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity. Hill and Wang, p. 97

- ^ Bessel, R. (1993). Germany after the First World War. Oxford University Press, p. 42

- ^ Mosse, G. L. (1975). The Nationalization of the Masses: Political Symbolism and Mass Movements in Germany from the Napoleonic Wars through the Third Reich. Howard Fertig, p. 143

- ^ Jones, Larry Eugene. German Liberalism and the Dissolution of the Weimar Party System, 1918–1933. University of North Carolina Press, 1990, p. 215.

- ^ Nolan, Mary (1994). Visions of Modernity. American Business and the Modernization of Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 313. ISBN 0195088751.

- ^ Stanley G. Payne (1980). Fascism: Comparison and Definition. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299080648. p. 62.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler (2003), Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte. Bd. 4: Vom Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges bis zur Gründung der beiden deutschen Staaten 1914–1949. München, p. 390 f.

- ^ Jones, Larry Eugene (1997). "Hindenburg and the Conservative Dilemma in the 1932 Presidential Elections". German Studies Review. 20 (2): pp. 241, 244. doi:10.2307/1431947. JSTOR 1431947.

- ^ Robert Solomon Wistrich (2002). Who's who in Nazi Germany. Psychology Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-415-26038-8.

- ^ Hoffmann, P. (1996). The History of the German Resistance, 1933–1945. Harvard University Press, p. 312

- ^ Mommsen, H. (2009). Alternatives to Hitler: German Resistance under the Third Reich. I.B. Tauris, p. 184

- ^ Evans, R. J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin, p. 276.

- ^ Jaschke, H.-G. (2013). Entstehung und Entwicklung des Rechtsextremismus in der Bundesrepublik, Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 116ff.

- ^ Grumke, T., & Wagner, B. (1984). Handbuch Rechtsradikalismus. Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 428ff.

- ^ Grumke & Wagner, 1984, p. 429.

- ^ BT-Drucksache 14/1446. (1999) Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Ulla Jelpke et al. Retrieved from http://www.stade.vvn-bda.de/stahl.htm

- ^ VVN-BdA Stade. (2003). Neofaschistischer »Der Stahlhelm e.V.« hat sich selbst aufgelöst!. Retrieved from https://www.stade.vvn-bda.de/st-helm.htm

- ^ Winkler, H. A. (2006). Germany: The Long Road West, Volume 2: 1933–1990. Oxford University Press, p. 245.

- ^ Orlow, D. (1969). The History of the Nazi Party: 1919–1933. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 121.

“The Stahlhelm's commitment to German nationalism was expressed in its call for the restoration of German pride and sovereignty, often through rearmament and rejection of the Treaty of Versailles.”

- ^ Evans, R. J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin. p. 141.

“The Stahlhelm did not merely seek to restore the old order; it aimed at a total renewal of Germany along militarized and ultranationalist lines, rejecting any compromise with democracy or pluralism.”

- ^ Winkler, H. A. (2006). Germany: The Long Road West, Volume 1: 1789–1933. Oxford University Press. p. 389.

“Hugenberg’s DNVP viewed Der Stahlhelm as its unofficial army. The two shared a contempt for the Weimar Republic, longing instead for a restoration of the old order, militarism, and an authoritarian state.”

- ^ Waite, R. G. L. (1952). Vanguard of Nazism: The Free Corps Movement in Post-War Germany 1918–1923. Harvard University Press. p. 230.

“Nationalism for the Stahlhelm meant the defense of the Volk against Marxism, foreign influence, and the democratic principles of Versailles. It was a spiritual continuation of the Kaiserreich, wrapped in uniform and steel.”

- ^ Bessel, R. (1987). Political Violence and the Rise of Nazism: The Storm Troopers in Eastern Germany 1925–1934. Yale University Press. p. 19.

“Der Stahlhelm was imbued with a strong nationalist and monarchist ideology and attracted veterans who were disillusioned with the democratic Republic. It saw itself as the true guardian of German honor after the disgrace of Versailles.”

- ^ Bessel, R. (1987). Political Violence and the Rise of Nazism: The Storm Troopers in Eastern Germany 1925–1934. Yale University Press. p. 19.

“Der Stahlhelm held fast to a vision of a unified, powerful Germany, untainted by defeat and republicanism. Its nationalism was deeply linked to militarism and a mythic memory of the front-line community.”

- ^ Evans, R. J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin. p. 141.

“The Stahlhelm’s nationalism was based on war commemoration, loyalty to the nation above party, and a visceral hatred of the November Revolution which it saw as a stab in the back”

- ^ Winkler, H. A. (2006). Germany: The Long Road West, Volume 1: 1789–1933. Oxford University Press. p. 389.

“The Stahlhelm was part of a broader nationalist consensus that regarded the Treaty of Versailles as not just unjust but unnatural—its members openly called for the reoccupation of the Polish Corridor and the reassertion of German influence in East Prussia and beyond.”

- ^ Evans, R. J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin. p. 140.

“Groups like Der Stahlhelm... championed the idea of Drang nach Osten—the push to the East—as part of Germany’s historic destiny, aligning with broader nationalist fantasies of colonizing Eastern Europe and reversing the defeat of 1918.”

- ^ Waite, R. G. L. (1952). Vanguard of Nazism: The Free Corps Movement in Post-War Germany 1918–1923. Harvard University Press. p. 230.

“In Stahlhelm circles, the idea of reclaiming German soil lost in the East—particularly in Silesia and Posen—was a frequent theme in speeches and parades. They saw the East not only as lost land but as a field for future German colonization.”

- ^ (Peukert, 1992, p. 104)

- ^ (Orlow, 1969, p. 122)

- ^ (Mommsen, 1996, The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, p. 295)